Coming into the third quarter of 2020, the pandemic is still with us, and the Southern and Western U.S. are both experiencing a resurgence of the virus. For those keeping up with the latest headlines, there’s been no shortage about the fallout in the U.S. economy. Gross domestic product (GDP) declined 4.8% in the first quarter and the Federal Reserve expects that GDP will decline more than 30% in the second quarter. Although COVID-19 case counts slowed through April and many parts of the country shifted focus to reopening, the recovery is starting to look “W”-shaped for the South and West.

On the government front, after enacting the nation’s largest-ever fiscal stimulus package at the end of March (worth more than $2 trillion), Congressional leaders stopped short of announcing another relief package, though there have been rumors a new one could be geared towards state and local governments. Indeed, Congress has debated the merits of more fiscal stimulus given the rebound in economic data. However, according to the National Governors Association, states need another $500 billion in federal aid to make up for lost revenue. The U.S. Conference of Mayors says cities need about $250 billion.

On the government front, after enacting the nation’s largest-ever fiscal stimulus package at the end of March (worth more than $2 trillion), Congressional leaders stopped short of announcing another relief package, though there have been rumors a new one could be geared towards state and local governments. Indeed, Congress has debated the merits of more fiscal stimulus given the rebound in economic data. However, according to the National Governors Association, states need another $500 billion in federal aid to make up for lost revenue. The U.S. Conference of Mayors says cities need about $250 billion.

Unsurprisingly, given the economic shutdowns and increased costs of managing a pandemic, many state and local governments are facing severe declines in tax revenues and have (if not have already) started cutting payrolls to manage their finances. Looking at the numbers, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports state and local government employment declined by about 1.5 million since February 2020 to about 18 million currently. At the moment, most of the losses appear to be state education and local government (excluding education) related.¹ As a recent Wall Street Journal article reports, state and local governments are primarily cutting money for education as coronavirus-induced recession wreaks havoc on their finances and they adhere to laws requiring balanced budgets. For now, it seems many have plugged budget holes by tapping reserves or cutting expenditures. Positively, many municipalities went into the pandemic-induced recession with healthy reserves bolstered by a decade-long economic expansion.²

Even so, it seems the financial markets are paying little attention to economic warning signs, amid Federal Reserve stimulus and Monday’s announcement from China that fostering a “healthy” bull market is important.

Yield Control?

Since cutting the fed funds rate to zero in mid-March, the Federal Reserve has deployed extraordinary measures of quantitative easing (QE) to ensure markets function smoothly and remain liquid. Initially, this amounted to purchasing treasuries and agency/government-guaranteed mortgage bonds. The Federal Reserve then also implemented new programs to purchase corporate bonds and municipal bonds and make “Main Street” loans to mid-size businesses. For sure, these expansions beyond the boundaries of the Fed’s previous dalliances with QE are unprecedented, but the intent is to keep liquidity flowing to households, businesses, and local governments. For perspective, prior to the pandemic, the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet was under $4 trillion. It has now ballooned to over $7 trillion, and it is expected to continue climbing higher. Yet some market pundits are now talking about yield curve control, sometimes called interest rate caps – repeating a policy the Fed last used during and after WWII.

In normal times, the Fed attempt to influence economic conditions by raising or lowering very short-term interest rates, e.g. the overnight rate at which banks lend excess reserves to each other. Under yield curve control (YCC), the Fed would target some longer-term rate and pledge to buy enough bonds to keep the rate from rising above its target, which could stimulate the economy if cutting short-term rates to zero isn’t enough. Although somewhat similar to QE, QE focuses on quantities of bonds whereas YCC targets prices of bonds. Meaning, under QE, the Fed could say it plans to buy $1 trillion in Treasury securities. Because bond prices have an inverse relationship to their yield, buying bonds pushes up their prices, which leads to lower long-term rates. Under YCC, the Fed commits to buy whatever amount of bonds is necessary to maintain certain interest rate levels along the yield curve.

To be clear, the Fed stated in its June 2020 meeting notes that it is not planning to implement a YCC policy and is more inclined to continue using forward guidance and QE. And the most interesting point mentioned in the Fed minutes was a reluctance to create a situation where the use of a yield curve target might mean that monetary policy goals ”come in conflict with public debt management goals, which could pose risks to the independence of the central bank.” However, some market pundits believe because the economic recovery is slowing in areas with resurgences of the virus and so long as our healthcare system is unable to effectively manage the virus, we are likely to see a W-shaped recovery. And every time the economy stalls, the Fed will be under pressure to do something and quickly.

Municipal Yields Have Returned to Pre-Pandemic Levels as Investors Return to the Market

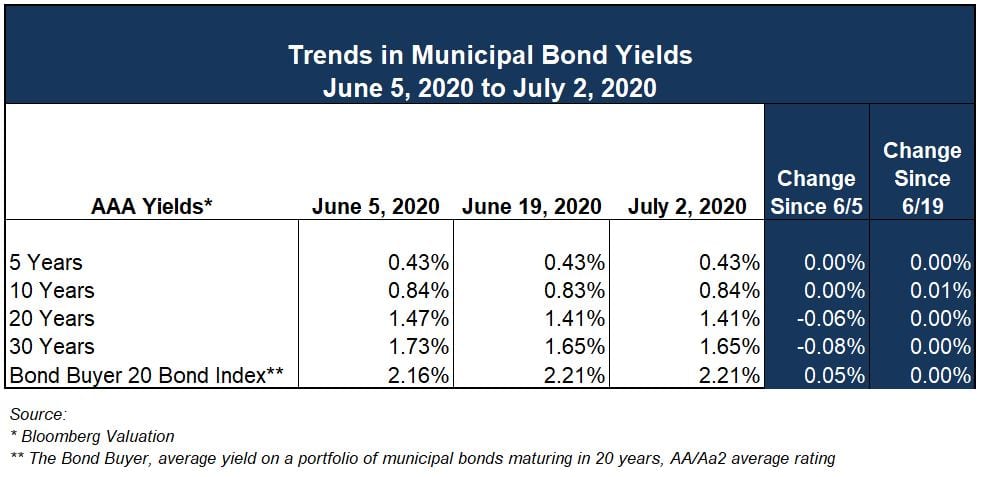

Expectations for a swift economic recovery, which has been supported by upside surprises in data releases, were dampened as the Miami-Dade region in Florida become the latest virus hot spot to re-impose restrictions on business activity. However, it seems municipal bond yields continue to remain steady, as they have for at least the past couple of weeks. MMD and other yield indices have barely changed, mostly ending the week within a basis point of where they started.

As we have reported previously, over the past ten months, the 10-year Treasury has moved from 2.00% to 0.70% (and today (July 9th) to about 0.60%), which however you want to measure that, is a pretty dramatic decline. For municipal bonds, the decline has also been fairly steep but nowhere near as dramatic as Treasuries. And now munis consistently exceed Treasuries when only 6 months ago the 10-year muni yield was 70% of the 10-year Treasury yield; for reference, at the time of writing, the 10-year muni to Treasury ratio was calculated at 140.5%, reflecting the risk premium investors are putting on state and local government securities. Indeed, given the stress COVID-19 has put on state and local government finances, investors are taking a keener look at credit quality and financial flexibility. However, on a positive note, yields are still very low when compared to historical standards and not too far from their recent low point earlier this year.

¹ https://www.bls.gov/web/empsit/ceshighlights.pdf

Required Disclosures: Please Read

Ehlers is the joint marketing name of the following affiliated businesses (collectively, the “Affiliates”): Ehlers & Associates, Inc. (“EA”), a municipal advisor registered with the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board (“MSRB”) and the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”); Ehlers Investment Partners, LLC (“EIP”), an investment adviser registered with the SEC; and Bond Trust Services Corporation (“BTS”), holder of a limited banking charter issued by the State of Minnesota.

This communication does not constitute an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any investment (including without limitation, any municipal financial product, municipal security, or other security) or agreement with respect to any investment strategy or program. This communication is offered without charge to clients, friends, and prospective clients of the Affiliates as a source of general information about the services Ehlers provides. This communication is neither advice nor a recommendation by any Affiliate to any person with respect to any municipal financial product, municipal security, or other security, as such terms are defined pursuant to Section 15B of the Exchange Act of 1934 and rules of the MSRB. This communication does not constitute investment advice by any Affiliate that purports to meet the objectives or needs of any person pursuant to the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 or applicable state law. In providing this information, The Affiliates are not acting as an advisor to you and do not owe you a fiduciary duty pursuant to Section 15B of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. You should discuss the information contained herein with any and all internal or external advisors and experts you deem appropriate before acting on the information.