Last week the Federal Reserve’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) once again cut its policy rate target by 25 basis points. The federal funds target range is now 1.75% to 2.00%. Similar to July (when the FOMC most recently cut the target rate), futures markets had already priced in the move prior to the action. Notably, however, there were three dissents from FOMC voting members: two felt the cut was unnecessary and one preferred a much larger rate cut.

The Fed’s summary of economic projections changed very little, and in his press conference, Chair Powell sounded upbeat about the economic outlook. Once again, he described the rate cut as insurance against trade uncertainty and a weakening global economy, not as the second step in a longer easing cycle. Economically, the Fed sees GDP growth slowing from 2.2% in 2019 to 2.0% in 2020 and below 2.0% in 2021 and 2022. It also forecasted little change in unemployment or core inflation in the near future.

Another Fed Cut in 2019?

Although the Fed rate cut last week was expected, the additional policy commentary provided some thought-provoking insight into the divergence of opinions. When asked about their policy expectations for the rest of 2019, 7 members thought there should be one more cut, 5 believed no more rate adjustments would be necessary, and 5 expected a rate hike. The market, however, believes there will probably be another quarter-point rate cut before the end of the year.

Spike in Repo Rates

The most recent significant development in financial markets happened early last week when there was a spike in the repo market, prompting concerns over the amount of liquidity in the short-term market. But first, what is the repo market and why does it even matter? The repo market is where piles of cash and pools of securities meet and how banks and major financial institutions lend to one another (primarily overnight) to meet their day-to-day financing needs. “Repo” refers to repurchase agreements, (which are in essence short-term loans) that are collateralized by high credit quality and liquid securities, like U.S. Treasuries. Repo transactions allow parties that have excess cash to earn interest by lending that cash to those that need it. The borrower posts collateral with a third party to secure the loan. The borrower then effectively “repurchases” those securities at a slightly higher cost, which equates to the imputed amount of interest earned by the lending party.

What happened last week? In short, there wasn’t enough cash for those who needed it – meaning, there was a lack of cash in the system to accommodate the demand for repo. As a result, this imbalance caused repo rates to spike from about 2.0% last week to over 10.0% intraday. Perhaps more alarming for the Fed (which entered the market in 2013 on a large scale, effectively putting a floor under rates) was how volatility in the repo market pushed the effective federal funds rate to 2.30%, above its target range of 2.00% – 2.25%. This occurred just as the FOMC was getting ready to lower the fed funds target to 1.75% – 2.00%. In response, the Fed injected about $200 billion in temporary cash (excess bank reserves) to push the repo rate down, which is the first direct injection of cash to the banking sector since the financial crisis. The injection helped to calm markets, bringing the rate back down to around 2.0%.

Why did this even happen? According to some, the liquidity squeeze was due to a trifecta of pressures:

- Payments on corporate taxes were due on September 15th, leading to redemptions of more than $35 billion in money market funds and other cash-like investment products.

- The cash balance in the U.S. Treasury general account increased by $83 billion, thus reducing excess reserves and the supply of overnight market liquidity available.

- Primary dealers needed an additional $20 billion in funding to finance the settlement of recently-auctioned U.S. Treasuries.

That said, some economists and market participants are saying this volatility signals a longer-term problem. Some believe the rules regulators imposed after the financial crisis caused broker dealers to reduce market-making activities and the holdings of securities on their collective balance sheets, reducing market liquidity. Others think that banks don’t have enough excess reserves parked at the Fed. The combination of both factors seems to have diminished the usual “cushions” in times of market stress. All in all, there is some concern over the Fed’s ability to control money markets and its ability to steer the economy in this period of post-crisis monetary policy.

What’s next? As previously mentioned, some economists believe total bank reserves are insufficient and the Fed may have to start buying bonds again to boost reserves. When the Fed buys securities, those cash proceeds create reserves in the system. At the same time as it injected capital into the banking system, the Fed announced a cut in the interest on excess reserves (IOER) of 0.30% (5 basis points more than the cut in the fed funds rate) to incentivize banks to lend out more of their money. If banks can earn the same amount of interest by leaving excess reserves with the Fed as they could investing it in the market, there is no impetus to deploy those reserves into the real economy. Reducing IOER would help keep the repo rate stable and the effective federal funds rate within the Fed’s target range.

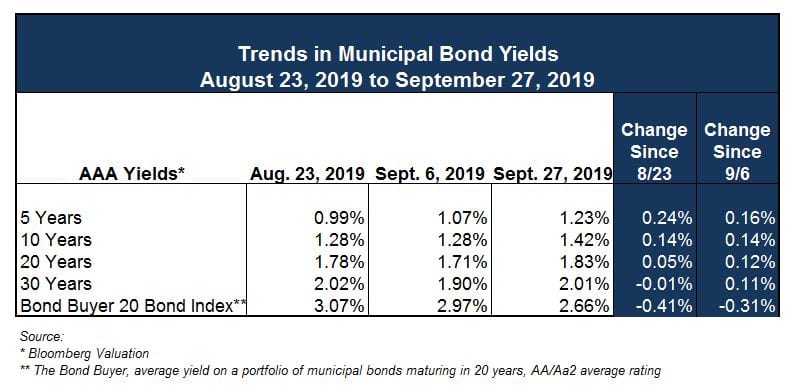

Trends in Muni Yields

In a continuation of a trend, both the municipal bond and Treasury markets traded higher last week, as some buyers interpreted the recent dramatic sell off as a buying opportunity – meaning, U.S. Treasury yields fell last week. That said, the direction of municipal yields was generally mixed last week, with short-term yields inching higher by a couple of basis points and longer-term yields falling 1 – 5 basis points.

There still seems to be strong demand for munis in the retail sector, as evidenced by inflows to long-term mutual funds and ETFs, which have been positive for the past 9 consecutive months. Some investors expect municipal supply to increase the last part of this year as the effects from tax reform subside and more municipalities take advantage of low rates to refund prior obligations, but it seems large swings in supply or demand are unlikely.

IMPORTANT INFORMATION: PLEASE READ

The information contained herein reflects, as of the date hereof, the view of Ehlers & Associates, Inc. (or its applicable affiliate providing this publication) (“Ehlers”) and sources believed by Ehlers to be reliable. No representation or warranty is made concerning the accuracy of any data compiled herein. In addition, there can be no guarantee that any projection, forecast or opinion in these materials will be realized. Past performance is neither indicative of, nor a guarantee of, future results. The views expressed herein may change at any time subsequent to the date of publication hereof. These materials are provided for informational purposes only, and under no circumstances may any information contained herein be construed as “advice” within the meaning of Section 15B of the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934, or otherwise relied upon by you in determining a course of action in connection with any current or prospective undertakings relative to any municipal financial product or issuance of municipal securities. Ehlers does not provide tax, legal or accounting advice. You should, in considering these materials, discuss your financial circumstances and needs with professionals in those areas before making any decisions. Any information contained herein may not be construed as any sales or marketing materials in respect of, or an offer or solicitation of municipal advisory service provided by Ehlers, or any affiliate or agent thereof. References to specific issuances of municipal securities or municipal financial products are presented solely in the context of industry analysis and are not to be considered recommendations by Ehlers.